CLEAR item#13

“Data source (e.g., private, public). State the data source (e.g., private, public, mixed [both private and public]). State clearly which data source is used in different data partitions. Provide web links and references if the source is public. Give the image or patient identifiers as a supplement if public data are used.” [1] (from the article by Kocak et al.; licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Reporting examples for CLEAR item#13

Example#1. “In collaboration with Radboud University investigators, we retrospectively analyzed the testing cohort of the publicly available imaging dataset from the PROSTATEx2 challenge, which included clinical MRI examinations and nonpublicly revealed histological grading results.” [2] (from the article by Michallek et al.; licensed under CC BY 4.0)

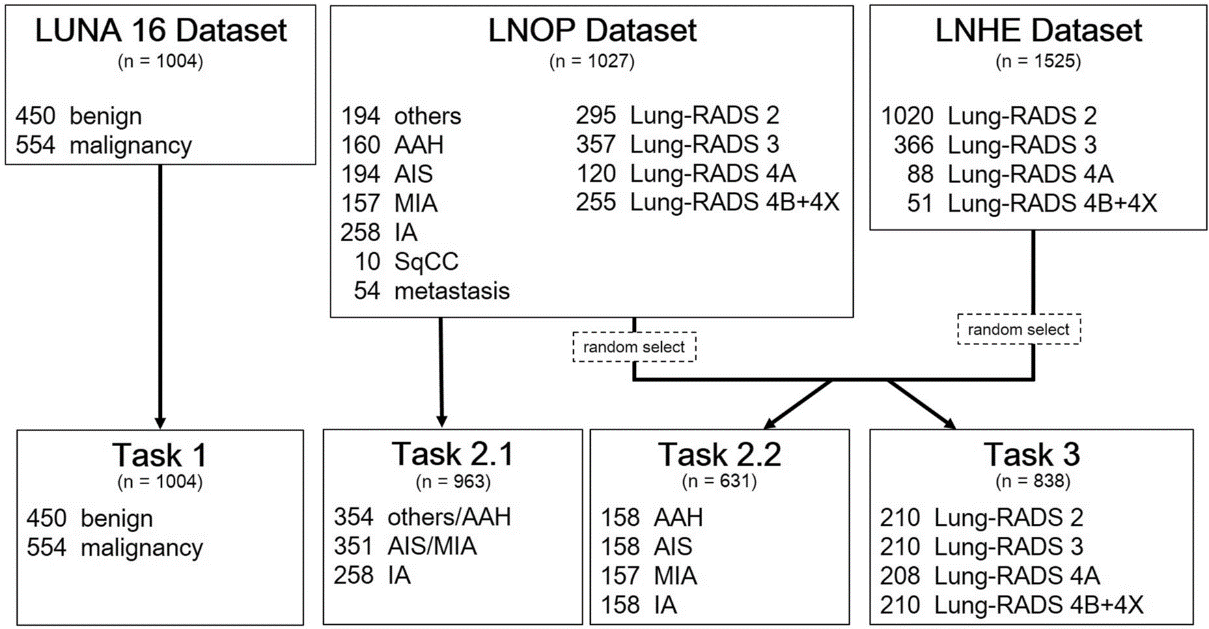

Example#2. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. “Flowchart of the analysis cohort.” [3] (from the article by Lin et al.; licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Explanation and elaboration of CLEAR item#13

In item#13, the main point is on elucidating the data source, distinguishing between private and public origins. Authors are strongly encouraged to precisely specify the data source as private, public, or a combination of both (mixed), for ensuring ethical transparency [4]. Furthermore, it is crucial to explicitly state whether distinct data sources were utilized in various data partitions or tasks (see Example#2), accompanied by web links and references. This transparency is vital for accurately interpreting the study’s results. Unique characteristics within different datasets can significantly impact the performance of radiomic features or predictive models. A thorough understanding of these nuances guarantees that the conclusions drawn from the study are appropriate and contextually relevant. Moreover, if the data are public and involve images or patient identifiers, it is important to include these details as supplementary information. This approach ensures a comprehensive and transparent representation of the data used, aligning with best practices in research integrity [5].

References

- Kocak B, Baessler B, Bakas S, et al (2023) CheckList for EvaluAtion of Radiomics research (CLEAR): a step-by-step reporting guideline for authors and reviewers endorsed by ESR and EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 14:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-023-01415-8

- Michallek F, Huisman H, Hamm B, et al (2022) Accuracy of fractal analysis and PI-RADS assessment of prostate magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of cancer grade groups: a clinical validation study. Eur Radiol 32:2372–2383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08358-y

- Lin C-Y, Guo S-M, Lien J-JJ, et al (2023) Combined model integrating deep learning, radiomics, and clinical data to classify lung nodules at chest CT. Radiol Med (Torino). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-023-01730-6

- Scapicchio C, Gabelloni M, Barucci A, et al (2021) A deep look into radiomics. Radiol Med (Torino) 126:1296–1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-021-01389-x

- van Timmeren JE, Cester D, Tanadini-Lang S, et al (2020) Radiomics in medical imaging—“how-to” guide and critical reflection. Insights Imaging 11:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-020-00887-2