Condition #2

“Does the study include fully automated segmentation?” [1] (licensed under CC BY)

Explanation

“Fully automated segmentation refers to the segmentation process without any human intervention.” [1] (licensed under CC BY)

Examples from the literature meeting “Yes” condition

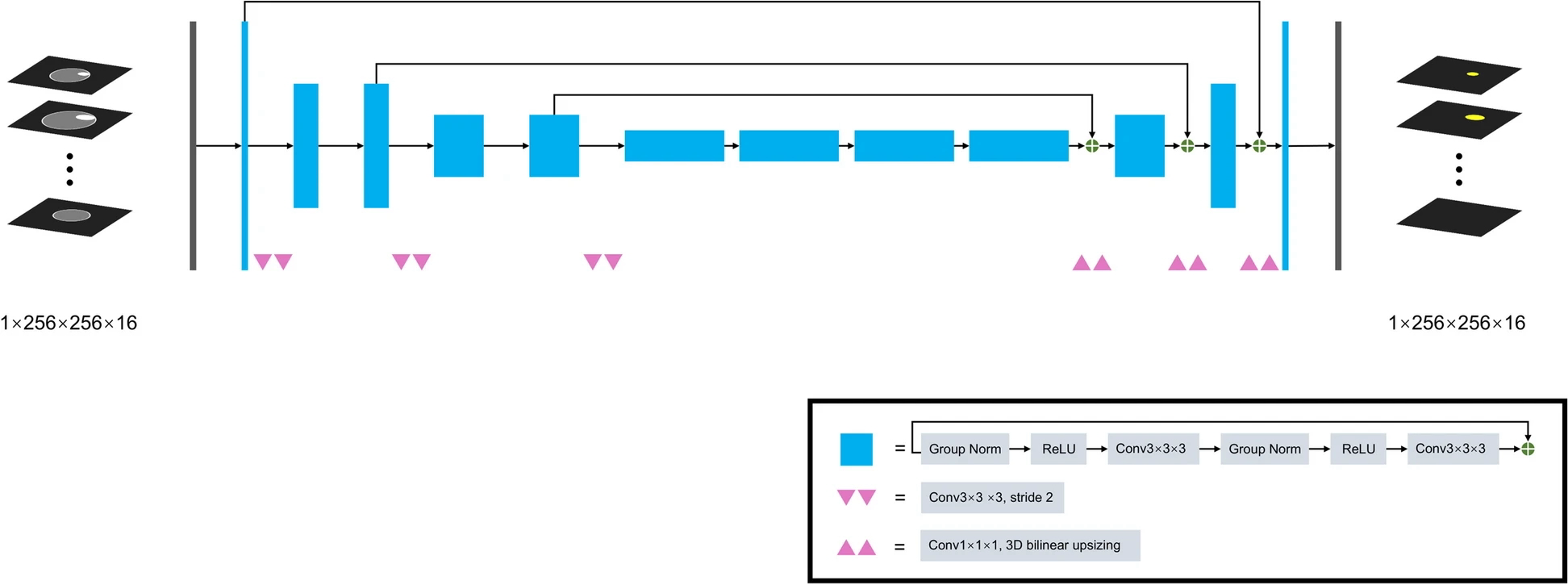

Example #1: “SegResNet, a 3D U-net-like network with a ResNetlike block, was applied to develop the automatic segmentation model, whose code was available on GitHub (https://github.com/Project-MONAI/MONAI). The architecture of this algorithm is shown in [Figure 1].” [2] (licensed under CC BY)

Figure 1. “SegResNet architecture” [2] (licensed under CC BY)

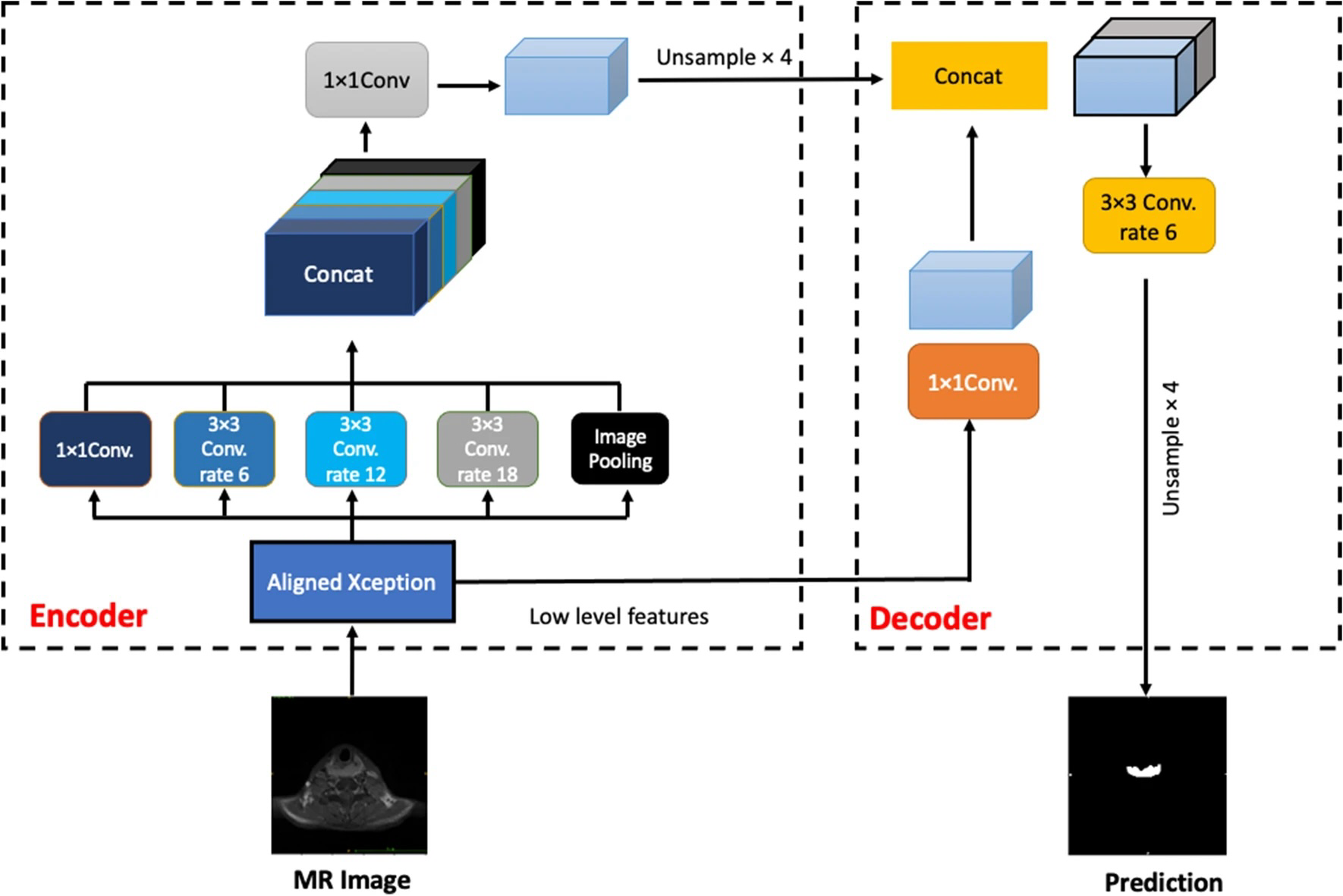

Example #2: “Two types of network architectures were used for training and testing the performances of tumor segmentation: the U-Net as previous studies, and DeepLab V3 + [Figure 2], a decoder module with a depth separable convolution for ASPP layers to improve the object boundary detection. The networks were trained with weight randomization and stochastic gradient descent Adam optimizer method. The signal intensities of all images were normalized to a mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1. The learning rate was set to 0.001, and the number of epochs until convergence was 100 with batch sizes of 2. The network was trained using Keras 2.1.4 written in Python 3.5.4 and TensorFlow 1.5.0. The code for the DeepLab V3 + model is available at https://github.com/bonlime/keras-deeplab-v3-plus.” [3] (licensed under CC BY)

Figure 2. “An illustration of the DeepLabV3 +. The encoder module encodes multi-scale contextual information by applying atrous (dilated) convolution at multiple scales, while the simple yet effective decoder module refines the segmentation results along object boundaries” [3] (licensed under CC BY)

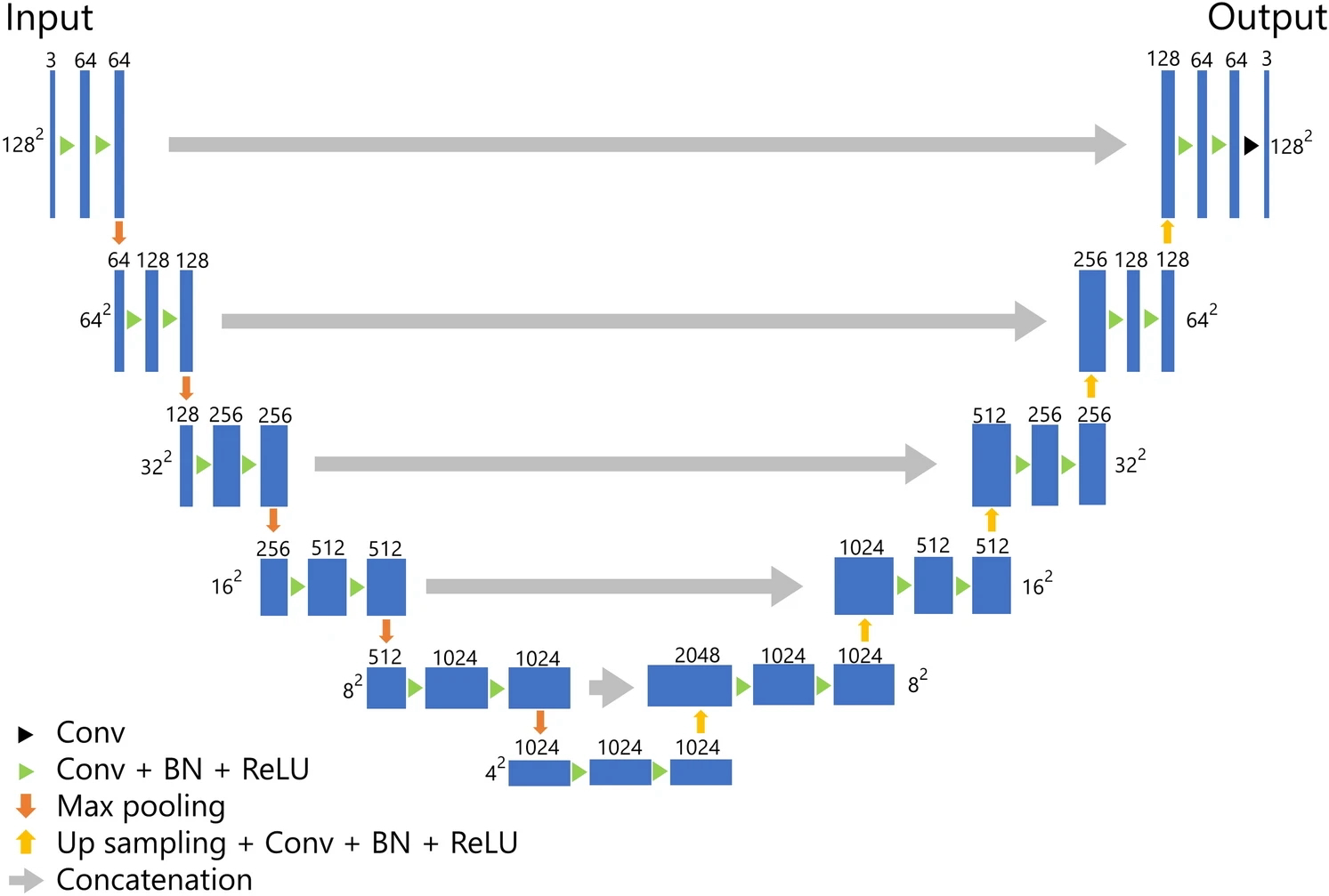

Example #3: “The architecture of our U-net-based model for the segmentation of BC is presented in [Figure 3]. Our model was composed of five layers, which was deeper than the original U-net composed of four layers. For training the model, we employed the Adam optimizer as the optimizer with the cost function of Dice loss. The epochs, batch size, and initial learning were set to 30, 56, and 0.001, respectively. During the training, we performed five-fold cross-validation using 80% of the patients for training and 20% for validation.” [4] (licensed under CC BY)

Figure 3. “U-Net architecture. Conv convolution, BN batch normalization, ReLU rectified linear unit.” [4] (under CC BY)

Hypothetical examples meeting “No” condition

Example #4: A deep learning-based segmentation model was developed using a modified U-Net architecture. The model was trained on a dataset of 500 contrast-enhanced MRIs. Following automatic segmentation, two experienced radiologists manually refined the segmentations to correct misclassified regions, particularly in cases with low contrast boundaries. These refined segmentations were used for feature extraction in the radiomic analysis.

Example #5: We implemented a deep learning-based segmentation pipeline using a 3D V-Net architecture to segment brain tumors from FLAIR MRI images. Before applying the model, images were preprocessed through manual ROI selection by an expert neuroradiologist to exclude non-relevant regions. After automatic segmentation, a morphological post-processing step was applied, where radiologists adjusted the contours of the segmented regions to improve the boundary definition before feature extraction.

Importance of the condition

In radiomic research, one major issue is data reproducibility, with segmentation being a crucial aspect [5–7]. Manual segmentation is time-consuming and prone to variability, impacting the reproducibility of radiomic features [8, 9]. Fully automated segmentation, meaning no manual modifications are performed, using deep learning models could help address this issue [10, 11]. Fully automated segmentation models must undergo external dataset evaluation to ensure their robustness and generalizability across different imaging settings [5, 12]. Additionally, their segmentation accuracy should be rigorously validated against expert radiologist annotations (e.g., Dice similarity coefficient, Jaccard Index, and intra-class correlation) to confirm their reliability [13, 14].

Specifics about the examples meeting “Yes” condition

Example #1 employs an automatic segmentation algorithm within a radiomic pipeline, incorporating a clinical endpoint. In contrast, Examples #2 and #3 focus solely on automatic segmentation, evaluating its accuracy and impact on the reproducibility of radiomic features. Additionally, the papers from which these examples originate provide detailed descriptions of fully automated segmentation, supported by illustrations.

Specifics about the examples meeting “No” condition

In Example #4, even though an automatic segmentation model was used initially, the study included manual refinement of the segmentations by radiologists. This human intervention means the segmentation process was not fully automated, leading to the same reproducibility concerns that affect manual segmentations. In Example #5, The segmentation process involved manual preprocessing (ROI selection) and post-processing (contour adjustments). Since human intervention occurred at multiple stages, the segmentation cannot be classified as fully automated.

Recommendations for appropriate scoring

Condition #2 should be classified as “Yes” only if the segmentation process is entirely automated, meaning no human intervention occurs at any stage. This includes both initial segmentation and any potential post-processing adjustments.

Conversely, Condition #2 should be classified as “No” if any manual intervention occurs after the automated segmentation, including adjustments to refine or correct the results. It should also be marked as “No” if the study uses semi-automated segmentation with human oversight or corrections or if the method includes manual pre-processing or post-processing steps that impact the final segmentation outcome.

Thus, even if an automated algorithm is used initially, any subsequent manual refinement renders the segmentation non-fully automated, and Condition #2 should be marked as “No.”

References

- Kocak B, Akinci D’Antonoli T, Mercaldo N, et al (2024) METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS): a quality scoring tool for radiomics research endorsed by EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 15:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-023-01572-w

- Yang L, Wang T, Zhang J, et al (2024) Deep learning–based automatic segmentation of meningioma from T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI for preoperative meningioma differentiation using radiomic features. BMC Medical Imaging 24:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-024-01218-3

- Lin Y-C, Lin G, Pandey S, et al (2023) Fully automated segmentation and radiomics feature extraction of hypopharyngeal cancer on MRI using deep learning. Eur Radiol 33:6548–6556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-09827-2

- Moribata Y, Kurata Y, Nishio M, et al (2023) Automatic segmentation of bladder cancer on MRI using a convolutional neural network and reproducibility of radiomics features: a two-center study. Sci Rep 13:628. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27883-y

- Kuhl CK, Truhn D (2020) The Long Route to Standardized Radiomics: Unraveling the Knot from the End. Radiology 295:339–341. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200059

- Klontzas ME (2024) Radiomics feature reproducibility: The elephant in the room. European Journal of Radiology 175:111430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2024.111430

- Stanzione A, Cuocolo R, Ugga L, et al (2022) Oncologic Imaging and Radiomics: A Walkthrough Review of Methodological Challenges. Cancers 14:4871. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194871

- Rizzo S, Botta F, Raimondi S, et al (2018) Radiomics: the facts and the challenges of image analysis. Eur Radiol Exp 2:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41747-018-0068-z

- Kocak B, Yardimci AH, Nazli MA, et al (2023) REliability of consensus-based segMentatIoN in raDiomic feature reproducibility (REMIND): A word of caution. European Journal of Radiology 165:110893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2023.110893

- Yamashita R, Nishio M, Do RKG, Togashi K (2018) Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology. Insights Imaging 9:611–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-018-0639-9

- Cheng PM, Montagnon E, Yamashita R, et al (2021) Deep Learning: An Update for Radiologists. RadioGraphics 41:1427–1445. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2021200210

- Yu AC, Mohajer B, Eng J (2022) External Validation of Deep Learning Algorithms for Radiologic Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 4:e210064. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.210064

- Tripathi S, Wadhwani R, Rasool A, Jadhav A (2023) Comparison Analysis of Deep Learning Models In Medical Image Segmentation. In: 2023 13th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence). IEEE, Noida, India, pp 468–471

- Minaee S, Boykov YY, Porikli F, et al (2021) Image Segmentation Using Deep Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3059968