Item #27

“External testing” [1] (licensed under CC BY)

Explanation

“Whether the model is tested with independent data from other institution(s). This also applies to the studies validating the previously published models trained at another institution.” [1] (licensed under CC BY)

Positive examples from the literature

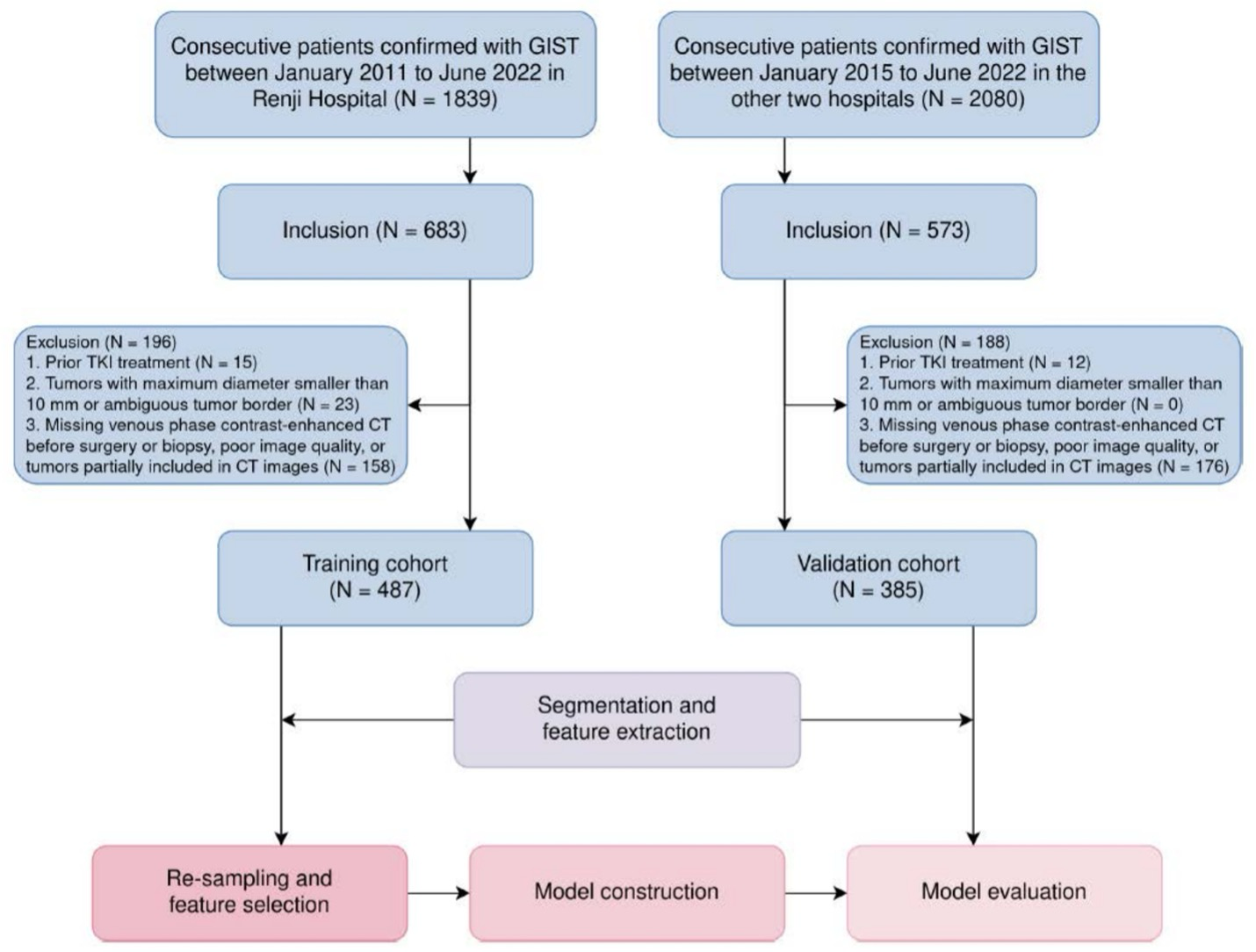

Example #1: “From January 2011 to June 2022, a total of 872 patients were retrospectively included in the study. These patients were divided into the internal training cohort (n = 487) from one center, and the external validation cohort (n = 385) from the other two centers.” [2] (licensed under CC BY)

Also see Figure 1.

Figure 1. “Patient recruitment and study workflow. CT, computed tomography; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumors; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitors” [2] (licensed under CC BY)

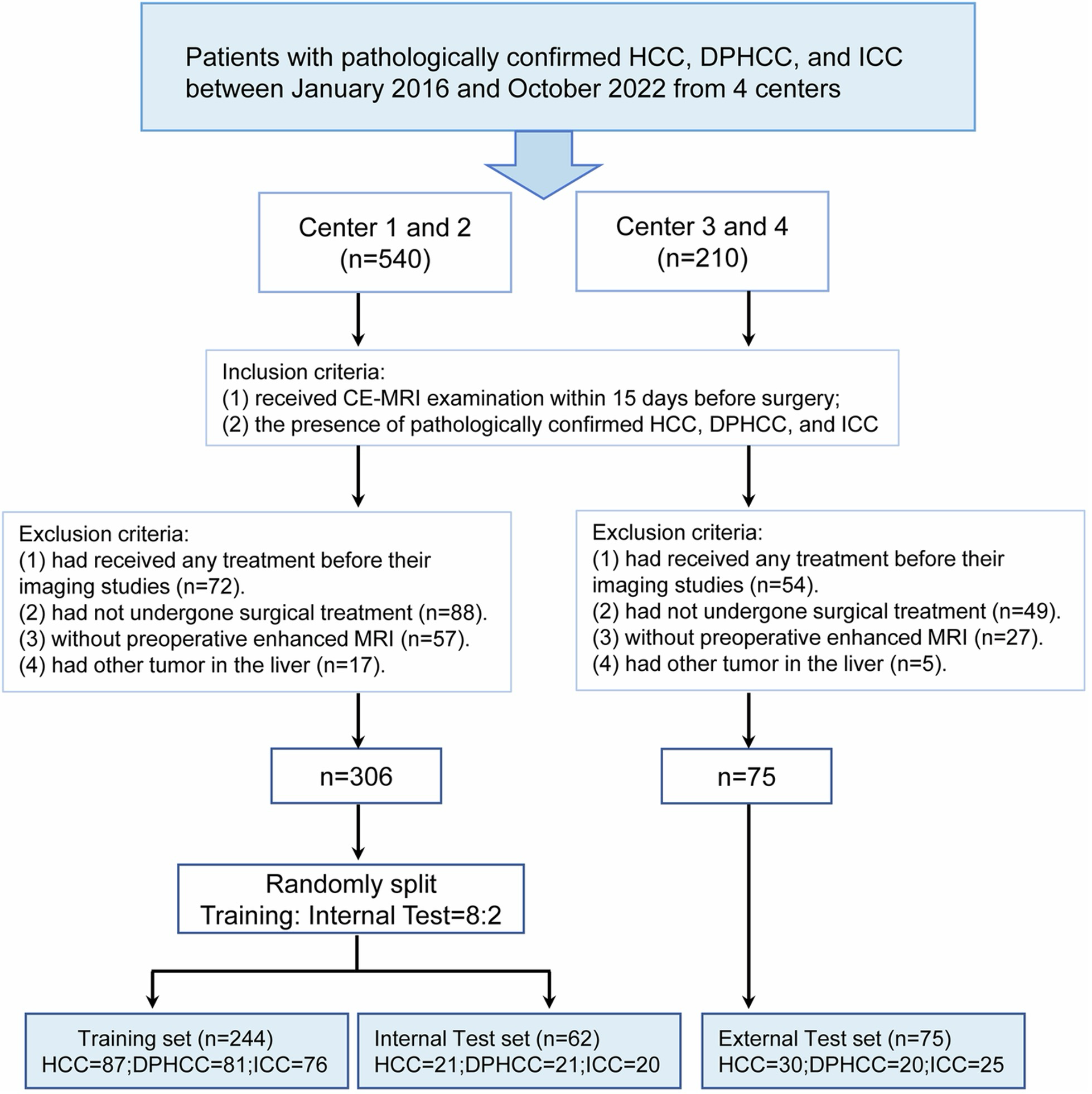

Example #2: “This study consecutively included patients from the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (center 1), the Affiliated Nantong Hospital 3 of Nantong University (center 2), the Tangshan People’s Hospital (center 3), and the First People’s Hospital of Taicang (center 4) who received CE-MRI from January 2016 to October 2022. […] The patients from centers 1 and 2 were divided into a training set and internal testing set at a ratio of 8:2 via stratified random sampling, and the patients from centers 3 and 4 were used as an independent external testing set. A flowchart of patient inclusion and exclusion was shown in [Figure 2] in this study.” [3] (licensed under CC BY)

Figure 2. “Patients’ flowchart for this study. Key inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; DPHCC, dual-phenotype hepatocellular carcinoma; ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; CE-MRI, contrast-enhanced MRI” [3] (licensed under CC BY)

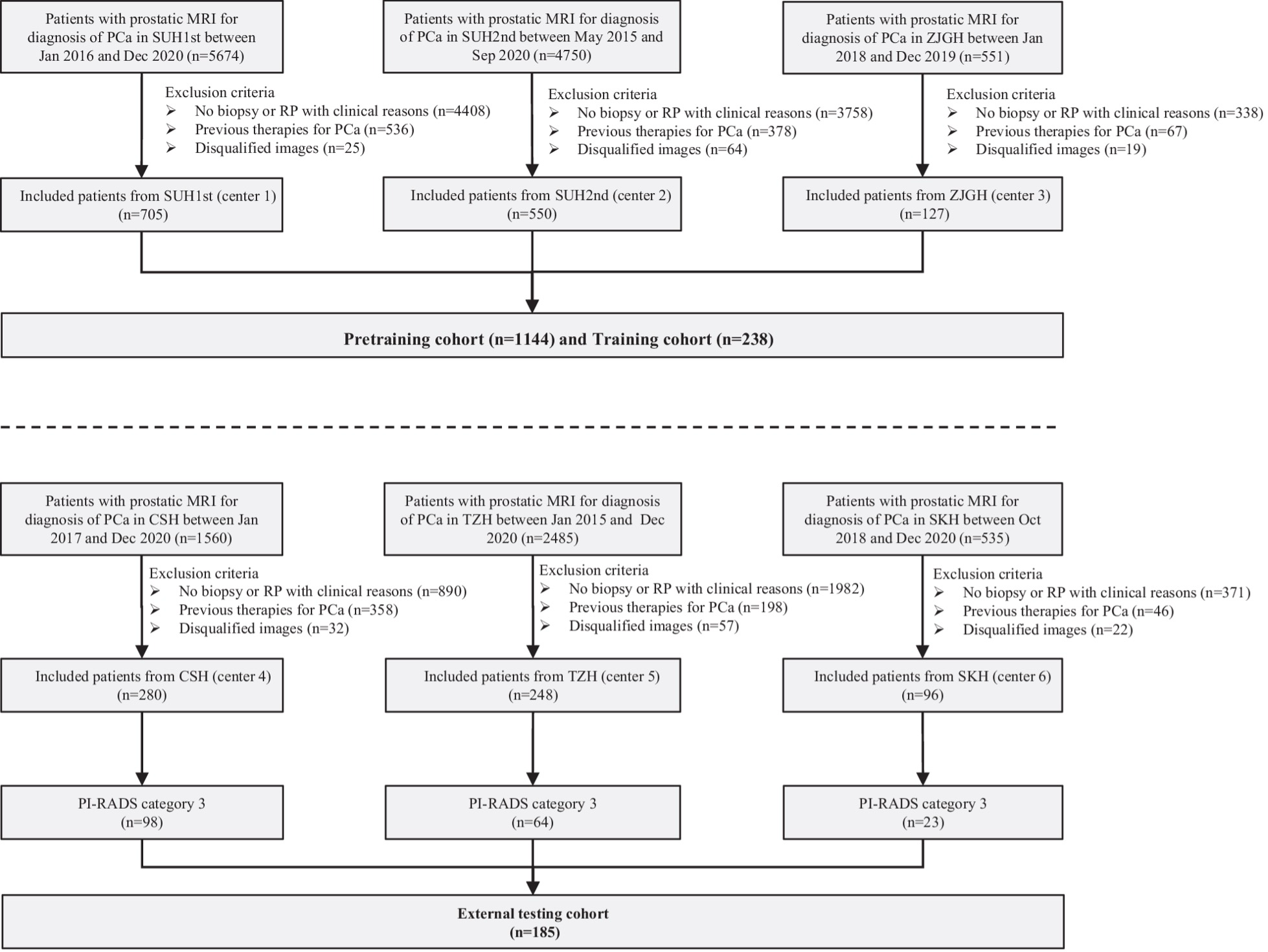

Example #3: “Patients with PI-RADS 1, 2, 4, and 5 of centers 1–3 were used as a pretraining cohort (total N = 1144), and PI-RADS 3 patients from the same centers were used as the training cohort (total N = 238). For centers 4–6, PI-RADS 3 patients were used as external testing cohorts (total N = 185) [Figure 3], and PI-RADS 1, 2, 4, and 5 patients (N = 439) were not applied in the present study. In each pretraining and training cohort, the patients were randomly divided into two datasets, including nine-tenth (i.e., the training dataset) and one-tenth patients (i.e., the tuning dataset), which were used to train the network weights and optimize the hyperparameters of the DL model, respectively.” [4] (licensed under CC BY)

Figure 3. “Flowchart of the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria of the multicenter study. center 1, SUH1st, the first affiliated hospital of Soochow University; center 2, SUH2nd, the second affiliated hospital of Soochow University; center 3, ZJGH, People’s Hospital of Zhangjiagang; center 4, CSH, Changshu no. 1 People’s Hospital; center 5, TZH, People’s Hospital of Taizhou; center 6, SKH, Suzhou Kowloon Hospital; PCa, prostate cancer” [4] (licensed under CC BY)

Hypothetical negative examples

Example #4: A total of 650 patients undergoing procedure X at University Hospital between January 2017 and December 2021 were included. The dataset was chronologically split: patients from 2017-2020 (n=520) were used for model development (training and internal tuning via 5-fold cross-validation), and patients from 2021 (n=130) formed the ‘external validation’ cohort to assess final model performance. The model showed promising results on this external set.

Example #5: Data from 900 patients were collected retrospectively from three participating sites: Site A (n=400), Site B (n=300), and Site C (n=200). This combined dataset was then randomly partitioned into a training set (n=720) and a test set (n=180). The model was trained on the training set and evaluated on the test set.

Importance of the item

In radiomics studies, as in all scientific research, well-designed external testing is crucial for validating a model’s performance on independent datasets not used during training, thereby mitigating the risk of overfitting [5]. This step ensures that the model can reliably identify patterns across diverse populations, scanners, and imaging protocols, demonstrating its potential for broader clinical application.

According to METRICS [1], which was developed through an extensive international modified Delphi process, external testing was assigned the second-highest quality weight—nearly ten times greater than the lowest-weighted items. This highlights its fundamental role in ensuring the robustness and generalizability of radiomics models. Literature terms vary in the use of the terms “validation” and “testing” so both “external testing” and “external validation” have been interchangeably used. According to the CLEAR guideline for radiomics research and CLAIM 2024 update, external testing should be established as terminology to avoid confusion [6, 7].

Specifics about the positive examples

All three positive examples clearly demonstrated the presence of external test sets from institutions independent of those used for model development. Example #2 and #3 provided additional clarity by specifying the names of all the centers, making the assessment even more transparent. Furthermore, all examples facilitated evaluation by incorporating well-structured flowcharts, ensuring a clear and systematic presentation of the study design.

Specifics about the negative examples

In Example #4, all data originates from a single institution. Although split temporally and incorrectly labeled “external validation,” the test set is not from an independent institution, which is required for true external testing.

In Example #5, data from all participating sites were pooled before splitting into training and testing sets. Consequently, the test set is not institutionally independent; it contains a mix of patients from the same sites used for training, rather than being composed solely of data from site(s) separate from the training data sources.

Recommendations for appropriate scoring

To appropriately score studies for external testing, it is essential to confirm that an independent institutional dataset was designated for this purpose. Accurate use of terminology is critical, as some studies may incorrectly label a simple hold-out set as “external validation,” despite being conducted within a single center. Therefore, the origin of the datasets must be carefully scrutinized to ensure that the external test set genuinely originates from a different institution. Studies that misclassify internal data splits as external validation should not receive a point for external testing according to METRICS criteria.

References

- Kocak B, Akinci D’Antonoli T, Mercaldo N, et al (2024) METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS): a quality scoring tool for radiomics research endorsed by EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 15:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-023-01572-w

- Xie Z, Zhang Q, Zhang R, et al (2024) Identification of D842V mutation in gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on CT radiomics: a multi-center study. Cancer Imaging 24:169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-024-00815-3

- Wu Q, Zhang T, Xu F, et al (2025) MRI-based deep learning radiomics to differentiate dual-phenotype hepatocellular carcinoma from HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicenter study. Insights into Imaging 16:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-025-01904-y

- Bao J, Zhao L, Qiao X, et al (2025) 3D-AttenNet model can predict clinically significant prostate cancer in PI-RADS category 3 patients: a retrospective multicenter study. Insights into Imaging 16:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-024-01896-1

- Koçak B (2022) Key concepts, common pitfalls, and best practices in artificial intelligence and machine learning: focus on radiomics. Diagn Interv Radiol 28:450–462. https://doi.org/10.5152/dir.2022.211297

- Kocak B, Baessler B, Bakas S, et al (2023) CheckList for EvaluAtion of Radiomics research (CLEAR): a step-by-step reporting guideline for authors and reviewers endorsed by ESR and EuSoMII. Insights into imaging 14:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-023-01415-8

- Tejani AS, Klontzas ME, Gatti AA, et al (2024) Checklist for artificial intelligence in medical imaging (CLAIM): 2024 update. Radiology Artificial intelligence 6:e240300. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.240300